Tag Archives: calories

Very low calorie diets in diabetes: the Bournemouth experience

Pat Miles, David Kerr

Introduction

The therapy of obese patients with poorly controlled diabetes is a complex area. Despite the best efforts of healthcare professionals and patients, therapy is too often associated with repeated failure, which can give rise to frustration and sometimes despondency. Very low calorie diets (VLCDs) have been advocated for this population group. This article looks at the process and outcomes of one VLCD programme. The results support the wider adoption of VLCDs, but there are significant resource implications which are also discussed.

The treatment of the obese individual with poorly controlled diabetes is a common and perplexing problem. Wading in with ever increasing amounts of insulin without giving thought to ameliorating the inevitable weight gain will cause desperation in the multidisciplinary team and despondency in the patient. Very lowcalorie diets (VLCDs), of <800 kcal perday, are designed to achieve substantial weight loss while preserving lean body mass and are typically associated with a 20 kg weight reduction in three months (NTFPTO, 1993). Unfortunately, regain of half to two-thirds of the initial weight loss is common within 12 months after cessation of the diet, although there may be longer term benefits in terms of a reduction in the need for medication in obese individuals with diabetes (Wing et al, 1994). Recently, Paisey et al (1998) compared VLCD with a traditional intensive dietary regimen in 30 obese (BMI>30) patients with diabetes and 19 obese controls without diabetes. After four months of VLCD, subjects were switched to a low-fat diet and continued to be seen weekly by the multidisciplinary team. Weight loss was substantial and maintained after cessation of VLCD (mean 14kg at 12 months), and 14 of the 15 patients who had chosen VLCD had normal blood glucose and fructosamine levels despite stopping all medication. For four patients with recent-onset diabetes, normalisation of blood glucose levels was sustained for 12 months.

Study aim

A pilot study was carried out to examine the effect of a VLCD programme on a group of obese (BMI30) patients with diabetes. These patients remained obese despite enormous efforts by the multidisciplinary team (including primary care). Usually, there was also poor glycaemic control. Method Between January and June 1999, 24 patients aged 29–76 years were enrolled into Lipotrim (Howard Foundation Research, Cambridge, England), a VLCD programme which gives 450 kcal per day for women and 600 kcal per day for men. For entry to the programme, each patient had to:

- Understand the programme

- Desire to take partUndertake to attend weekly individual and group sessions

- Have family support

- Be desperate or determined to lose weight.

The product was available from the hospital at a cost of £18 per week for women and £24 per week for men. The expenditure for each patient was offset against money saved by not purchasing normal food. Lipid-lowering medication was stopped on entry to the programme. Weight, blood pressure and urinary ketones were measured once weekly up to refeeding then weight and blood pressure were measured at every patient contact thereafter. Lipid levels and HbA1c were measured at the start of the programme, every month for the first six

months then at three-monthly intervals for the next six months. Patients were expected to attend the individual and group sessions at each visit (every week). In the individual sessions with the nurse, patients could discuss any problems they had encountered (Figure 1). Group sessions provided support, an opportunity to exchange experiences and preparation

for refeeding. The dietitian was involved around the time of refeeding, to reinforce product literature from the company. Most patients refed at 3–4 months, and then followed a low fat healthy eating plan. After refeeding, follow up continued weekly for the first month, then every 2–4 weeks (frequency at the patient’s discretion). However, group sessions stopped at six months into the programme.

Results

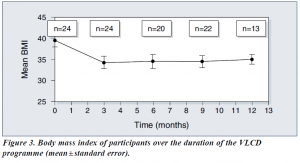

Average body mass index (BMI) was 39.5 at the start of the study.

Of the 24 patients:

- 16 were being treated with insulin

- 14 were hypertensive and were receiving appropriate medication

- 14 had dyslipidaemia and were receiving appropriate medication

- 2 were suffering from sleep apnoea requiring continuous positive airways pressure

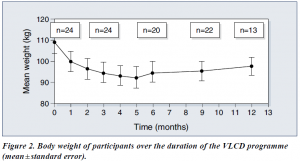

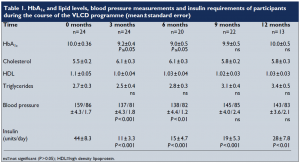

Following the introduction of VLCD, there were significant reductions in body weight (Figure 2) and BMI (Figure 3). Data on HbA1c levels, plasma lipids, blood pressure and insulin requirements of programme participants are shown in Table 1. Plasma lipid levels remained largely unchanged. Only four patients restarted lipid-lowering medication after refeeding.

Blood pressures dropped significantly within the first week, and adjustment of antihypertensive medication was necessary on a regular basis. Eleven patients stopped all antihypertensive medication. For most patients, ketone levels were moderate to high during the VLCD (indicating adherence to the programme and utilisation of fat stores). Insulin doses were decreased by two thirds on commencement of the programme, and this seemed to work well, with insulin doses continuing to decrease as weight loss proceeded. Most patients who remained on insulin were changed to nocte insulin

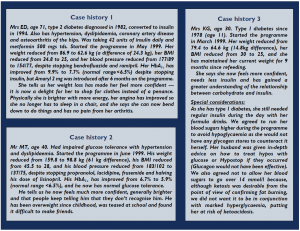

when their requirements were less than 14 units a day. Sulphonylureas were also halved or stopped on commencement of the programme. Only 13 patients completed follow up for the 12 months of the programme. The three case histories (see page 111) provide further detail about some of the patients in the programme.

Discussion

Benefits of VLCD

VLCDs can be an effective method of reducing weight, improving glycaemic control

— at least in the short term — and reducing the need for concomitant medication in

obese people with diabetes. They can also allow individuals to gain insights into the potential benefit of weight reduction and to learn about the relationship between food and obesity. When asked why this diet had worked while all others had failed, our patients said that it was easier to have no food at all, than to try to make choices from food offered, particularly on social occasions. Also the rapid weight loss experienced on the programme was positive reinforcement, together with the feeling of ‘wellbeing’ experienced as a consequence of ketosis (Burley et al, 1992).

Some considerations

It is well known, however, that helping someone to maintain weight loss is often the most difficult and disappointing task (Wing, 1995). In addition, the process is very time consuming for any healthcare professional involved. This pilot project to examine the effectiveness of VLCDs involved seeing 24 patients every week for 3–4 months, then at least monthly for the following nine months. We have only touched the ‘tip of the iceberg’ in our clinic population. If this service were offered to all of our obese patients (at least 60% of the total), a 50% uptake would involve 2250 patients who would require 11 whole time equivalent healthcare professionals just to provide weekly visits! In practice, this would be unrealistic and unlikely to attract funding, though one could argue that treating the root cause of the problem is far better than attempting to treat the effects. Putting VLCD into practice In many areas, primary care is offering Lipotrim to its obese patients. If the expertise of practice nurses and community dietitians in using this product could be built up, and the diabetes team was available for advice on medication changes for people with

diabetes, then it could be possible to offer this service more widely and cost effectively.

However, because of the additional risks of hypoglycaemia and ketoacidosis in patients with type 1 diabetes, we feel that they should only be offered the programme under the supervision of an experienced diabetes team, and then only if the patient is able to self-adjust insulin appropriately and understands the risks.

Conclusion

This study advocates the use of VLCDs for reducing weight and improving glycaemic control in obese people with type 2 diabetes (as well as carefully selected people with type 1 diabetes under close supervision). VLCDs can also reduce the need for concomitant medication. While on a VLCD, individuals can become empowered through their increased awareness and knowledge of their diabetes and the positive feedback provided by the rapid weight loss. It is likely that lack of time would limit the widespread adoption of the VLCD service used in this pilot study. However, the potential benefits of VLCD make it worthwhile to try to produce a costeffective service, perhaps by increased primary care involvement.

PDF Version: bournmouth-miles-kerr

AUDIT RESULTS USING THE LIPOTRIM PATIENT TRACKER BY PHARMACIST GARETH EVANS

Audit Results using the Lipotrim Patient Tracker

by Gareth Evans

The current excitement generated by the press coverage of the Newcastle University study of diabetic patients using weight loss by a very low calorie diet to “cure” diabetes, necessitates a wider recognition of the well established programmes already available. The Lipotrim weight loss programme, monitored exclusively by healthcare professionals has been in extensive use in the UK for more than 25 years. A rapidly expanding network of nearly 2000 pharmacies currently offer the VLCD service and although many have used manual methods to audit their patients’ achievements, the newly provided Patient Tracker computer software for managing patient records has permitted continuous auditing of results and detailed evaluation of population subsets.

For example, in addition to auditing the total experience of patients enrolled in the pharmacist-run service, the results can be examined in many different ways. The cohort can be divided by gender, by age, by initial or final BMI, by amount or percentage of weight loss achieved, or by medical history (hypertension, diabetes, depression, thyroid problems etc.). The programme extends beyond weight loss, as there is a refeeding transition back to ordinary foods and a full maintenance programme, which is proving extremely successful in the pharmacy environment. With this Tracker audit tool, therefore, evidence is also available documenting the long term maintenance outcome after dieting.

As a pharmacist who has been using the Tracker to keep my Lipotrim patients’ records for some time now, I would like to share a current audit of my patients’.

Materials and Methods

Overweight or obese people requesting the programme are assessed for suitability on the basis of initial BMI and a detailed medical history. Those requiring medical cooperation, such as those with type 2 diabetes or medicated hypertension make suitable arrangements with their GP prior to dieting or are excluded. Those with contraindicated conditions, such as insulin dependant diabetes or pregnancy are excluded from the programme.

Suitable candidates follow a strict regime of total food replacement using nutrient complete formulas, essentially very low fat enteral feeds, with adequate fluid intake and only black tea or coffee permitted in addition. Appropriate prescribed medications are continued as well. No other foods, beverages or supplements are permitted.

Dieters are monitored and weights recorded weekly – only 1 week’s supply of formulas can be obtained at each visit and obvious non-compliance is corrected or the dieter is offered alternative weight loss advice.

Records are maintained on the Patient Tracker programme.

Results

Total Population of Dieters completing 3 or more weeks on Total Food Replacement

Mean Start Weight 91 kg – Mean End Weight 81 kg

Total weight lost to date of audit – 3865 kg

Table 1 N= 382 330 Females 52 Males

| Mean | Start wt | 91kg | Start BMI | 32.7 | End BMI | 29.0 | % wt loss | 10.8 |

| Median | Start wt | 88.2 kg | Start BMI | 32.0 | End BMI | 28.4 | % wt loss | 9.0 |

The next series of tables demonstrates the value of the Lipotrim service in overweight patients, reducing the likelihood of their progression to obesity, as well as obese, super obese, morbid obese or even super-morbid obese patients.

Table 2 N= 121 BMI 25-30

| Mean | Start BMI | 28.1 | End BMI | 25.4 | % wt loss | 9.3 |

| Median | Start BMI | 28.3 | End BMI | 25.4 | % wt loss | 8.0 |

Table 3 N= 141 BMI 30-35

| Mean | Start BMI | 32.4 | End BMI | 28.9 | % wt loss | 10.9 |

| Median | Start BMI | 32.3 | End BMI | 29.1 | % wt loss | 12.0 |

Table 4 N= 73 BMI 35-40

| Mean | Start BMI | 36.9 | End BMI | 32.4 | % wt loss | 12.9 |

| Median | Start BMI | 36.7 | End BMI | 32.6 | % wt loss | 11.0 |

Table 5 N= 29 BMI 40-45

| Mean | Start BMI | 42.2 | End BMI | 36.1 | % wt loss | 14.4 |

| Median | Start BMI | 42.0 | End BMI | 36.3 | % wt loss | 11.0 |

Table 6 N= 5 BMI 45-50

| Mean | Start BMI | 47.4 | End BMI | 37.2 | % wt loss | 21.2 |

| Median | Start BMI | 47.3 | End BMI | 36.9 | % wt loss | 22.0 |

Other subsets of the patient information that are of interest include:

Table 7: Obese people who exceeded the 5% criterion for medical benefit of weight loss.

Tables 8and 8a: Some dieters choose to interrupt their diet for varied reasons and then return for a subsequent diet period. Their first and second dieting courses can be examined separately.

Table 9: After a period of weight loss, it is necessary to re-introduce carbohydrates in a controlled manner to minimise weight regain due to carbohydrate loading. Minimal weight change is expected despite reintroduction of normal foods. This phase is 1 week long.

Table 10: The Tracker software distinguishes between periods of dieting and maintenance providing evidence of minimal recidivism when patients are properly supported in the pharmacy environment.

Table 7 N= 231 BMI > 30 who lost 5% or more of initial weight

| Mean | Start BMI | 35.3 | End BMI | 30.8 | % wt loss | 12.7 |

| Median | Start BMI | 34.5 | End BMI | 30.1 | % wt loss | 11.0 |

Table 8 N= 78 Dieters who had 2 dieting courses First time

| Mean | Start BMI | 32.1 | End BMI | 29.1 | % wt loss | 9.0 |

| Median | Start BMI | 31.2 | End BMI | 28 | % wt loss | 7.5 |

Table 8a N= 78 Dieters who had 2 dieting courses Second time

| Mean | Start BMI | 31.1 | End BMI | 29.6 | % wt loss | 4.7 |

| Median | Start BMI | 29.7 | End BMI | 28.1 | % wt loss | 3.5 |

Table 9 N= 140 Refeeding week

| Mean | Start BMI | 27.5 | End BMI | 27.4 | % wt loss | -.2 |

| Median | Start BMI | 26.6 | End BMI | 26.6 | % wt loss | 0 |

Table 10 N= 249 Maintenance after dieting

| Mean | Start BMI | 28.1 | End BMI | 28.1 | % wt loss | 0.1 |

| Median | Start BMI | 27.2 | End BMI | 27.0 | % wt loss | 0 |

Patients who are medicated for various weight related ailments can often be considered as different categories of patient. Many hypothyroid patients have experienced great difficulty with weight management. Depression and hypertension often have a weight component in the aetiology of the problem.

Table 11: Examines patients on medication for hypertension

Table 12: Examines patients on medication for hypothroidism

Table 13: Examines patients on medication for Depression

Table 11 N= 22 Patients with High Blood Pressure

| Mean | Start BMI | 36.2 | End BMI | 32.0 | % wt loss | 11.6 |

| Median | Start BMI | 37 | End BMI | 32.2 | % wt loss | 8.5 |

Table 12 N= 9 Patients with thyroid hormone replacement

| Mean | Start BMI | 34.5 | End BMI | 29.4 | % wt loss | 14.2 |

| Median | Start BMI | 34.7 | End BMI | 28.9 | % wt loss | 10.0 |

Table 13 N= 13 Patients with Depression

| Mean | Start BMI | 33.2 | End BMI | 28.2 | % wt loss | 13.0 |

| Median | Start BMI | 32.2 | End BMI | 28.9 | % wt loss | 11.0 |

Discussion

The extreme flexibility of the Patient Tracker software, in addition to documenting and visualising each individual patient’s experience, allows for presentation of evidence of the weight loss achievements of cohorts of patients. This has become important for commissioning and the new ability of grouping patients from an individual surgery permits certification to the surgery of the collective progress of their patients, These results can be of value for CPD as well.

As can be seen from the multiple tables presented as illustration, the percentage of initial weight lost generally averages well over 5% and in most cases over 10%. Even the median values, which documents the half-way values of the ranges, are generally very close to the mean. Successful weight loss is found even in the extremely high BMI patients, who are usually refractory to weight management attempts.

In addition to demonstrating the successful loss of weight by the dieters, regardless of the sub-category for grouping, it is important to note that even though there are some variations in patients’ experiences with re-feeding (Table 9) and follow on maintenance (Table 10), the overall lack of weight regain from the patients post-diet demonstrates the value of the pharmacist and the Lipotrim programme for long term weight control.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that these results reflect the efforts of a single pharmacist in a programme that currently lists nearly 2000 pharmacies throughout the UK and Ireland, it is important to have the tools that can satisfy the need for documentation of achievement in this era of evidence-based treatments. The success of this pharmacy service has considerably enhanced my professional satisfaction as a pharmacist.

PHARMACIES LEAD THE WAY IN OBESITY MANAGEMENT

Pharmacists can play an important role in weight management.

And there’s evidence to support their effectiveness.

Early in October 2010, the National Obesity Forum Conference in London heard a presentation by Fin McCaul, the pharmacist at Prestwich Pharmacy in Manchester. Mr McCaul, who is also chair of the Independent Pharmacy Federation, was presenting his pharmacy’s outstanding results in treating overweight and obesity at the pharmacy. His paper, ‘Options for the orbidly obese’, was based on 1,148 overweight patients with a median initial BMI of 33.6 kg/m2

enrolled into the Lipotrim weight management programme. Of these patients, 25 per cent were morbidly obese with a BMI >40 kg/m2. At the time of audit, during which many patients were still actively dieting, the median BMI had decreased to <30 kg/m2. Results showed that 94 per cent of the dieters lost more than 5 per cent of their pre-diet weight, 47 per cent lost more than 10 per cent, and 21 per cent of the patients lost more than 20 per cent. The presentation highlighted the impressive weight loss results being achieved in pharmacy. Given that the organisers of the programme chose to position the presentation in the section of the conference devoted to bariatric surgery, Mr McCaul concentrated his results on the subset of the dieters who were of greatest relevance to the surgeons – the morbidly obese. Morbidly obese people are generally considered ‘heart sink’ cases; they are notoriously difficult to treat. The reason is largely due to the common chemistry with other examples of substance abuse. Recognition of this common chemistry is now leading to the development of weight management strategies involving drugs which are important in the treatment of alcohol and drug addictions.

Advantages of weight loss

Advantages of weight loss

There is certainly plenty of justification for helping overweight patients. Weight loss can lower blood pressure, normalise blood lipids, practically eliminate type 2 diabetes, reduce the severity of asthma, bring relief to arthritics, increase the fertility of women hoping for pregnancy, relieve sleep apnoea, and provide an opportunity for patients to be considered for Pharmacists can play an important role in weight management. And there’s evidence to support their effectiveness. elective surgery. Loss of weight can decrease the need for antidepressants, make exercise more possible – thus improving cardiovascular health, and can vastly improve the quality of life for patients. Methods of treatment, however, are not universally agreed upon. Somewhat unsurprisingly, bariatric surgeons tend to favour the surgical approach to weight loss. According to the Department of Bariatric Surgery at Imperial College, the current burden of morbid obesity in the UK is approximately 720,000 patients who meet NICE criteria for eligibility for surgery. In 2008 only 4,000 operations for morbid obesity were performed in the public and private sector combined. Even if the number of patients being treated by surgery was doubled, the impact on the problem would still be small and fall far short of the treatment needs of the seriously overweight population. Most surveys estimate that in the UK about 60 per cent of the population are overweight and about 30 per cent are already obese. Assuming a 60 million UK population, the number of people with a weight problem calculates to 36 million overweight and 18 million obese. Treating this many people surgically is unrealistic, to say the least. In addition, there is an increasing tendency for people to seek less expensive or more readily available bariatric surgery abroad, which has led to an ethical dilemma for NHS specialists. The costs to the NHS of providing aftercare, expected free by UK citizens, or emergency subsequent surgery when procedures initiated abroad go wrong, can be unplanned for and a substantial drain on NHS resources2.

Pharmacists’ role

Bariatric surgeons (in the current absence of a selection of effective weight loss drugs) are increasingly attempting to convince the public and the professionals that surgery is the only method of effectively treating seriously overweight people. The evidence presented by Mr McCaul clearly demonstrated that there is a non-invasive treatment that can be as effective. Like the claims for remission of diabetes as a result of the surgery, diabetes remissions are obtained by pharmacists as well since it is the loss of weight that leads to the remission. Usually, the blood sugar control is so rapid that it has become mandatory to get the doctor’s cooperation in stopping oral hypoglycaemic medications prior to the patient dieting. Without this step, patients are not permitted to participate in the Lipotrim programme. The results presented for this difficult cohort of morbidly obese patients was suitably impressive. These were very large individuals indeed, with half presenting with a BMI above 45 – the heaviest just below BMI 70. From this subset of 267 patients, the results reported were:

- Median BMI was 45.1 at enrolment;

- 237 patients lost over 5 per cent of pre-diet weight;

- 141 had lost over 10 per cent of pre-diet weight;

- 34 patients had lost over 20 per cent.

The programme at Prestwich is only one of more than 1,500 UK pharmacies treating overweight patients in this way. What’s more, the introduction of Lipotrim’s patient tracker software now permits on-demand audits of the results obtained by each pharmacy – essential for demonstrating effectiveness for commissioning requirements. Mr McCaul’s audience – primarily surgeons – listened for the most part in attentive silence, but the questions put to him at the end of his presentation were extremely revealing and illuminating. One overly distressed questioner was seriously worried that a few weeks of what is essentially a nutrientcomplete enteral feed (to effectively treat morbid obesity and its medical consequences) would compromise the patient’s relationship with food and cause chaos in the family dynamic. As she summed it up: there was a risk of “demonising food”. Leaving aside for a moment the point that bariatric surgery is an invasive and dangerous procedure that results in a state of permanent malnutrition, it is worth remembering that morbidly obese individuals generally have a very destructive relationship with food. To these individuals, food is a substance of obsession and addiction, and eating is a compulsive behaviour. Modifying the patient’s relationship with food is arguably a very worthwhile goal.

One of the more disturbing post-surgical problems (being widely reported from the US, where large numbers of surgeries are performed) is the unexpected and unwelcome problem of addiction transfer. A quick Google search unearths the massive scope of the problem, in which the loss of the ability to eat (due to weight loss surgery) is apparently leading to the development of substitute addictions – to alcohol, drugs and other destructive activities.

Total food replacement

Total food replacement

The total food replacement programme owes its success in no small part to the first principle that – instead of inducing malnutrition – the formulated enteral feeds are generally much more nutritious than the ordinary food choices of the

patients. As all essential nutrients are provided, the patients remain healthy throughout their programme. Where there

is a component of food abuse associated with the weight problem, the nutrient formulas are the only way that normal

foods – the addictive substances – can be safely eliminated so that the dieter can have a better chance of success.

An expanding network of pharmacists is offering a range of treatments for weight problems. Pharmacists have the training, the respect of the public, the contact hours and the desire to offer weight management as a professional service.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends that specialists be used for extended treatments involving total food replacement. Pharmacists that join this programme are trained and experienced specialists in this area.

Unlike surgery, there is no cost to the NHS, and no serious sideeffects.

The cost to the patient is less than the money a morbidly obese individual will have been spending on food, and the level of weight loss is sufficient to put type 2 diabetes into remission. The documented and audited successes of these dieters is a welcome testament to the leadership role that pharmacists are taking by providing important healthcare services to their community

PDF version: 1-6-pharmacist

WEIGHT MANAGEMENT

Pharmacists are emerging as the weight management specialists, providing advice, treatments and support for the long-term maintenance of weight loss. Stephen Kreitzman and Valerie Beeson offer some background information to help tie together the complex issues surrounding weight management

The primary fuel for normal meTabolism is sugar. This simple and well-established fact provides the key to an understanding of the complex and at times confusing issues associated with managing body weight.

Sugar

‘sugar’ is a confusing term right from the start, since in common usage sugar generally refers to sucrose, the usual sweetener found on the table. in fact, however, there are many different sugars. The lactose in milk and the fructose sugars found in fruit and honey are very common in our diets. a healthy, normal diet should generally provide about 60 per cent of its calories from sugars in one form or another. The form in which sugars are presented to the body does make a difference. This difference, however, is usually more important in the digestive tract. before a sugar can enter the bloodstream, it must be digested (broken down from complex forms such as polysaccharides or even 2 unit sugars such as sucrose or lactose) into single unit sugars and then transported actively by carrier mechanisms across the gut membranes. What actually enters the blood, therefore, are primarily the simple sugars, glucose, fructose and galactose. if we are slow or unable to digest these complexes of sugars, they are considered fibre and provide different benefits to the body other than calories. for calories, the important sugar is glucose.

Glycogen

Glycogen

since glucose is critical for normal energy provision in our cells, there is necessarily some storage and there are three primary storage sites. Glucose is stored in the human body in the liver, in muscles and, very important for the understanding of weight management, in the fat cells. When glucose is stored at these sites, it is stored in the form of a complex polymer of

glucose called glycogen. Glycogen fact: There is a lot more of it in the fat of overweight people than in normal weight people. it is stored in a very hydrated form – 3–5 parts of water per part of glycogen. This means that a pound of glycogen stored in the body actually weighs between 4–6lb on the scales. Conversely, using a pound of glycogen for energy will show up as a 4–6lb weight loss. The water is simply excreted.

Weight loss

Tracking the weight of a dieter losing weight on a lowcarbohydrate, low but constant calorie intake shows very rapid weight loss initially, which very smoothly slows as less and less of the daily fuel used is glycogen. after the glycogen is essentially depleted, the subsequent weight change per day is virtually linear, reflecting the constant 3,500-calorie deficit per pound of fat weight lost and the constant intake. The consequences of the early loss of glycogen and associated water are familiar to most dieters. The initial days of weight change are heady since glycogen, a carbohydrate contributing four calories per gram to the daily deficit, will need a deficit of only 1,800 calories to use up a pound of glycogen and release another 4–5lb of water weight. This makes weight loss seem easy. it is an illusion. not only is glycogen repleted after the restriction is finished, but if the reintroduction of carbohydrates to the diet is not done properly, the repletion can actually deposit excessive glycogen and water. This would be a weight gain.

Body weight or energy stores?

it is necessary to distinguish changes in body weight from changes in the energy content of the body. failure to do so has led to laxative abuse and diuretic abuse. but as we have just discussed, loss of substantial amounts of water weight can be achieved by carbohydrate restriction. it can even be achieved by intensive exercise with several pounds of sweat lost. making changes in the glycogen and water stores of the body can be dramatic, but should not be confused with a loss of weight that reduces the energy reserves stored in the body. While it is essential, regardless of the methods employed, to produce a calorie deficit and subsequent weight reduction, to first deplete the glycogen reserves, it should be clear that drastically reducing the intake of carbs will produce an initial weight loss regardless of the calorie content of the food consumed. it should be just as clear, however, that if the calorie content of the food is in excess of that used, the overall energy stored in the body will be increased even while there may be a measurable and possibly substantial weight reduction on the scales. This

is the same as a secured bank loan. it will be paid back. The lost water weight will be easily regained. in order to reduce the energy stores of the body it is absolutely necessary to consume less calories than are used.

Nutrients in a low-calorie regime

There is no secret or magic to weight management. The calories eaten have to be considerably less than those being used for a sustained period of time. but professionals understand that continued health of the patient requires the patient to consume all the essential nutrients necessary for life and health. This becomes increasingly difficult as the amount of food consumed is reduced. We eat collections of plant and animal material every day and if we maintain a varied selection of foods, we can feel reasonably confident that we are getting the complete array of essential nutrients. The plants and animals we choose for food, however, each have some of the essential nutrients required by man, but none have them all. To get the right amounts for sustained health it is absolutely essential that we eat in excess of 1,200 calories. not because there is some metabolic danger related to the low calories, but simply because eating foods with lower calorie totals cannot provide all the nutrients needed by people.

The myth

The myth

experience showed that dieters eating less than about 1,200 calories a day frequently became ill. so a myth arose that dropping calories below about 1,200 in order to lose weight was unhealthy. it was, but not because the calories were low. a fat person has an enormous store of calories available. no additional calories are really needed while dieting. Supplementing with the missing nutrients, however, permits dropping the calorie intake much further without harm, as long as there are reserves of fuel left in the body. Fuel for the body is limited to glucose (and stores as glycogen) and fat. an obese individual has about 37,000 calories in reserve for each stone of excess weight and therefore has no realistic need to eat more. They just need to get the essential nutrients. When these come from a nutrient-complete formula food, the results are ideal: complete nourishment in minimal calories, only those contributed by the essential nutrients.

Fat versus carbohydrate for energy storage

it is fortunate that we store most of our excess calories as fat rather than as carbohydrate. 7,000 excess calories stored as fat adds an extra 1kg to our body weight. storing the same excess calories as glycogen and water would add close to 10kg. it does mean, however, that lowering the body content of energy stored as fat is necessary and requires a larger calorie gap to achieve than is necessary for glycogen.

Weight loss services in pharmacy

Dealing with weight management as a professional service in the pharmacy is considerably more effective when dieters are made aware of the differences between weight loss and loss of fat. Dieters need to understand the components of their lost weight – glycogen and water usage before fat. They need to understand how to restore the correct physiological balances after a period of calorie restriction to minimise recidivism. They need to understand that excessive protein intake during dieting may inhibit the resorption and utilisation of excess skin.

They should understand that the health outcome after a period of calorie restriction depends on the quality of nourishment available during calorie restriction. simply considering calories and not the nutrient needs of the body will undermine overall health. and the pharmacist needs to understand that in the very fat person, the first 10 per cent or so of body weight lost is primarily glycogen, with minimal fat. The 10 per cent target is usually the beginning of the depletion of the excess energy stored in the body fat, not the endpoint.

Pharmacists are emerging as the weight management specialists, providing lifestyle advice, effective treatments and support, and follow-on help for the most difficult aspect of managing weight: the long-term maintenance of weight loss.

PFD version: 1-4-weight-management