S N Kreitzman PhD and V Beeson

(University of Cambridge, Howard Foundation Research, Cambridge, UK)

ABSTRACT

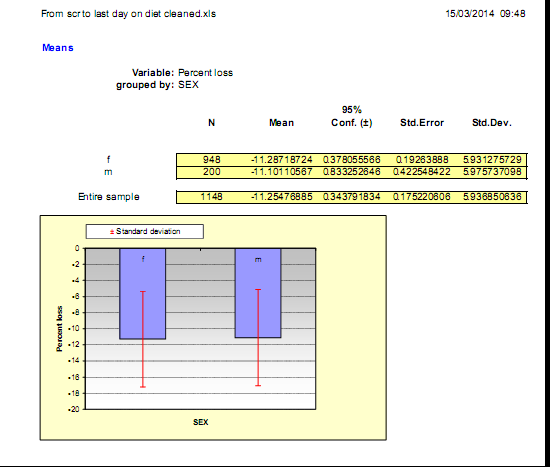

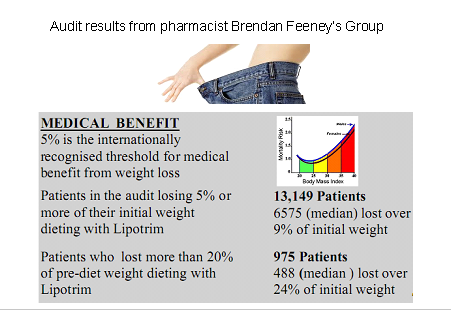

Objectives: To assess the weight losses and weight maintenance achieved with obese, often medically compromised, patients following a common Lipotrim treatment protocol.

Design: Data collation from voluntary responses by the practices to a general request for weight statistics, in a way that respects patient confidentiality. The sample of practices represents approximately 15% of those following the common protocol at the time of assessment.

Setting: 25 general practices and 2 hospital clinics in the UK.

Subjects: 818 obese patients registered with the practices or under medical referral to the hospital clinics The medical conditions ranged from apparently uncomplicated obesity to severely medically compromised patients, all treated under closely monitored conditions. Initial BMIs ranged from 24.4 to 78.7.

Interventions: Three, phased protocols, for weight loss, transitional refeeding and weight maintenance. Weight loss phase based upon Total Food Replacement under strict medical control – with specific, nutrient complete formula VLCD. Weight maintenance based upon modification of eating behaviour to significant dietary fat restriction. Considerable educational

materials provided throughout programme; approached conceptually as an addiction control problem.

Main outcome measures: Body weight and Body Mass Index at start of programme, at end of weight loss phase and the most recent follow-up available for each patient.

Results: Weight losses totalling in excess of 16,000kg with high levels of compliance and clinically encouraging weight maintenance results.

Conclusions: Obesity can be managed effectively under a variety of practice conditions, even in ‘heart sink’ patients who have repeatedly failed in the past to control their weight, despite the best efforts of the clinical team.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the prevalent academic knowledge of the medical problems associated with obesity (1-13), the frequent failure to achieve weight loss in obese patients has discouraged many practitioners from using weight loss as a primary treatment (2,18). Unless obesity is tackled, however, the scenario of a possible 25% of the population being obese by the year 2005 instead of the Health of the Nation target levels of 6 to 8 percent as in 1990 (14,15), will continue to be a health care frustration.

The impact of effective obesity treatment in general practice, however, is very dramatic. When patients with type II diabetes lose significant weight quickly, glycaemic control is improved better than the same weight loss achieved more slowly, and this appears robust even in patients where some weight is regained (7, 9, 10, 11, 16, 17).

In non insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), hypoglycaemic agents are generally stopped within a week or two (9). An impressive percentage of patients with hypertension have

also been able to reduce dosage or totally eliminate medication, often after only modest weight loss (7,11).

The impact of such major health improvement sin patients with long-standing and progressive disease provides the momentum for practices to continue to devote effort and resources to obesity management (25).

This paper reports a META-AUDIT of weight loss and maintenance results from ongoing obesity management programmes in UK general medical practice sites and hospital clinics following a common treatment protocol.

Total weight lost by 818 patients was 16,211kg (16+ tonnes).

METHODS

Meta-Audit

Weight information relating to the obesity control programmes was obtained from 25 UK general practices and 2 hospital clinics. Patients were not identified to the investigators, except by a sequential code number at each site. The information provided from each location included height, initial weight and date, end of weight loss phase (refeed) weight and date, and the last recorded follow-up weight and date. About half of the patients were still in the weight loss phase of the protocol at the time of the audit. This posed analytical dilemma. It was decided to treat the weight of those still dieting at the date of audit as if it were a refeed weight with a maintenance time of zero. Only in the separate maintenance data analysis does the category of

refeed refer purely to those patients who have completed their weight loss phase and resumed conventional food for at least one month.

PROTOCOL

At each site, patients join the programme solely at the medical discretion of the doctor who is versed in the protocol. In accordance with NHS practice, there is no financial consideration to the practice, from any source. The role of the GP is primarily the medical selection of appropriate patients and the monitoring of prescribed medications, which often have to be reduced or stopped as a result of the weight loss.

Patients are seen weekly, usually by a designated and trained practice nurse. In rare cases, extremely medically fragile patients are dieted and these cases are generally seen regularly by the GP. In general practice, the GP orders the Lipotrim formula foods weekly by positive release using a Special Order. This assures that patients cannot obtain the diet from the chemist without the knowledge and approval of the GP who is properly informed about the Lipotrim programme (26-28).

The Lipotrim is a nutrient complete very low calorie diet (VLCD) formulation. The diet is purchased from a local Pharmacist. This is the patient’s only access to the diet. Control of access is totally under the GP’s authority. Patients are expected to comply with the rigid diet and maintenance protocols. These are explained in detail by written material, video and audio taped sessions. Interactive lecture sessions are provided for patients and staff. Most practices limit the number of patients treated at any one time. Available places are rapidly filled from a waiting list.

Results

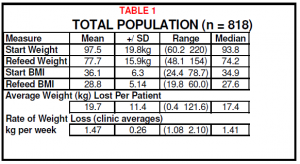

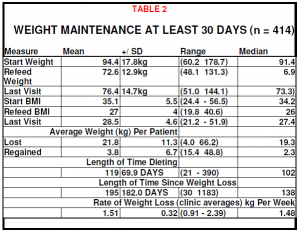

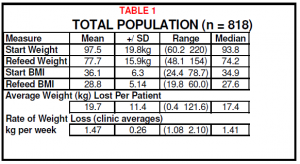

The results demonstrate that significant (Table 1) and sustained (Table 2) improvement in the weight of obese patients can be achieved under varied medical practice conditions.

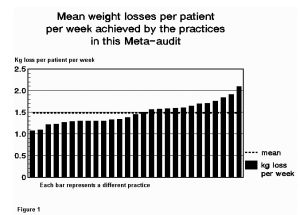

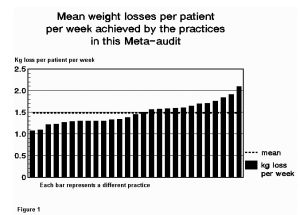

Individual practices were able to achieve a range of mean rates for weight loss in their patients (figure 1). The expected rate of weight loss for full compliance with the programme is an average of 1.46kg per week (1 stone per month). This was achieved.

MAINTENANCE

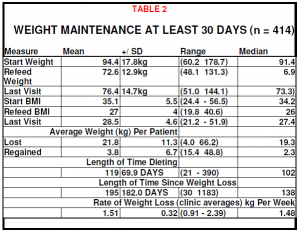

A subset of 414 patients, who had completed their weight loss phase at the time of audit and were attempting to maintained their weight, were evaluated.

MORBID OBESITY

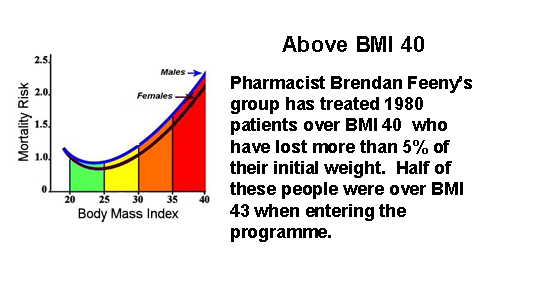

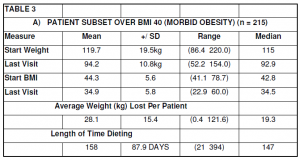

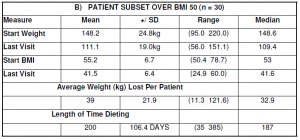

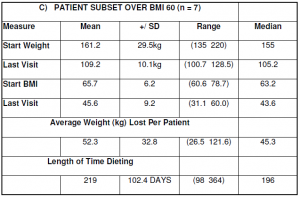

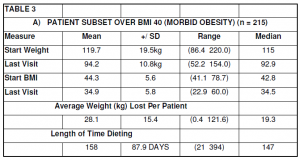

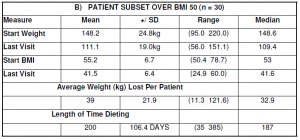

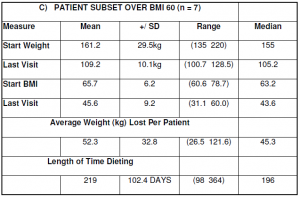

The clinical options for very fat people are limited. Most GPs despair of treating the massively obese. The population in this audit compilation included 215 patients over BMI 40, 30 patients over BMI 50 and 7 patients over BMI 60. Results from these patients are documented in Table 3 A-C respectively. Many of these patients are still in the weight loss phase (see Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The widespread apathy apparent in the general medical reluctance to deal with the obesity problem stems from a long history of futile efforts. Whether this is related to the ineffective modes of treatment offered, a general lack of understanding by either the patient or health professional, or a combination of both, is not clear. The prevailing view has become ‘diets do not work’ (18, 27). This view needs to be altered to reflect the very real difference between dieting protocols. Some standard weight reduction diets can work for some overweight patients. Applying the same approaches to the obese, however, will frequently result in failure. Obese patients require a more decisive treatment protocol (28). Rates of weight loss achieved per practice were shown in Figure 1.

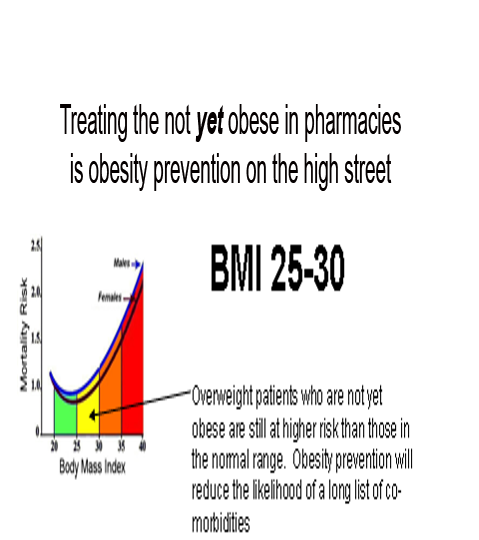

The premise that weight control is futile is unjustified and clinically insupportable when one considers that obesity itself is a risk factor for many serious clinical conditions (19). A large proportion of normal surgery time is spent dealing with many minor ailments, which are fundamentally weight related and which can escalate into serious disease when the weight problem reaches obesity (Body Mass Index >30) (20). Obesity occurring within a family unit can compromise the well being of that unit. The family ‘ill health’ is particularly problematic when the mother is obese. Depressive states and impaired quality of life (8) can affect a significant part of the patient’s daily routine and impact on the rest of the family members. A multiplicity of problems can be traced to obesity within the family.

Much is said about the need to educate and modify lifestyle (20), but the impact of dietary education is considerably grater when the patient is in a positive state of mind, with improved self esteem resulting from weight loss. Sedentary lifestyles are often a consequence of the excessive weight. With weight loss, most patients become significantly more active. This has been shown to increase the probability of maintenance of the lost weight (21).

For the obese, clinical weight goals may not necessarily be to achieve thinness. A more immediate goal may be to control elevated blood sugar or high blood pressure. It may be to allow

the patient access to certain surgical procedures, for blood lipid control or increased mobility or pain relief in an arthritic patient. Clinical judgement will require consideration of age, lifestyle and medical condition in setting realistic weight targets for an individual patient. The current ‘fashion figure’ is not the appropriate determinant of the weight target in the obese.

Weight regain needs to be put into perspective. The percentage of patients maintaining weight loss after medical obesity treatment far exceeds previous statistics (22). Long term weight maintenance at encouraging levels is now commonly reported for medical VLCD programmes (23,24), particularly when these include behavioural modification. There are no permanent cures for obesity. Despite this, an increasingly large number of patients can manage to maintain control for long periods after weight loss, albeit to varying degrees. A patient, however, who has lost 100kg and has regained 50kg is still 50kg lighter. This is particularly important where the lowered weight has allowed necessary surgery to be performed or improved another condition. The evidence of Wing, previously cited, and others (7, 11, 16, 17), suggests that some health benefits of weight loss (glycaemic control) can outlast the weight loss.

Dropout rates are important, but difficult to document. While the weight losses in this assessment are dramatic, no weight programme is universally successful. It is especially difficult to

assess the proportion of non-starters from the data available. The referral procedures into the programme vary widely from site to site. At some sites, access to the programmes is exclusively based upon the medical requirement for weight loss in an attempt to mitigate a pre-existing clinical condition. These referred patients are sometimes reluctant to comply or are disinterested in weight loss. In others, there is a component of self-referral, although the regulation of admission to the programme still remains entirely under the control of the practice. How many patients are referred to the programmes and decline participation cannot be estimated from the data available.

Also difficult to document accurately are the percentages of patients who attempt the protocol but find the initial days too difficult for their current level of motivation. Some practices

provided data from those patients who failed to attend beyond 1 week, but most did not.

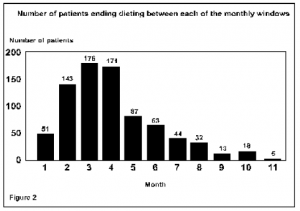

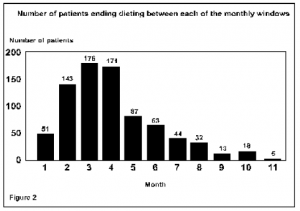

Our analysis, therefore, includes all patients who participated for at least 2 weeks. The data demonstrates that established patients complete the course. Figure 2 depicts the fraction of the 818 patients who stopped dieting within monthly intervals.

In Figure 3, the mean BMI changes for the subset of patients whoceased dieting within those monthly checkpoints are presented. Patients conclude dieting for many and varied reasons, only one of which is non-compliance and failure. These failures are included in the 6 percent (51 patients) of patients who discontinued during the first 4 weeks of treatment. Patients stop when they have achieved clinical goals, as discussed previously. It is evident from this graph that patients, on average, continue their weight loss programmes until they are no longer obese, regardless of their BMI at the start.

References

National Task Force. Very Low Calorie diets. JAMA 1993, 270, 8, 967974.

West KM. Diet Therapy of Diabetes: An Analysis of Failure. Ann Intern Med 1973, 79, 425434.

Anderson J W, Hamilton C C, Brinkman Kaplan V. Benefits and Risks of an Intensive Very Low Calorie Diet Programme for Severe Obesity. Am J Gastroenterology 1992, 87, 1, 615.

Chiang B N, Perlman L V, Epstein L V. Overweight and Hypertension: A review. Circulation 1969, 39, 403421.

Maxwell M H, Heber D, Waks A U, Tuck M L. The Role of Insulin and Norepinephrine.

Kannel W B, brand N, Skinner J J, Dawber T R, McNamara P M. The Relation of Adiposity to Blood Pressure and Development of Hypertension: The Framingham Study. Ann Int Med 1967, 67, 1, 4859.

Wing R R. Use of very low calorie diets in the treatment of obese persons with non insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Am Dietetic Assoc 1995, 95, 5, 569572.

Sarlio Lahteenkorva S, Stunkard A, Rissanen A. Psychosocial Factors and quality of life in obesity. Int J Obesity 1995, 19, 6, S1S5.

Paisey R B, Harvey P, Rice S, Belka I, Bower L, Dunn M, Paisey R M, Frost J, Goldman P, Ash I. Short term results of an open trial of very low calorie diet or intensive conventional diet in type 2 diabetes. Practical Diabetes Internat 1995, 12, 6, 263267.

Kirschner M A, Schneider G, Ertel N H, Gorman J. An Eight Year Experience with a Very Low Calorie Formula Diet for Control of Mahor Obesity. Int J Obesity 1988, 12, 6980.

Wing R R, Greeno C G. Behavioural and psychosocial aspects of obesity and its treatment. Ballier’s Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1994, 8, 3, 689703.

Office of Health Economics. Obesity 1994, 112.

Berg F F. Health risks of obesity. Obesity and Health 1993, 10-35.

The Health of the Nation. Department of Health. London HMSO, 1992.

The Health of the Nation. Health Survey for England 1991. Social Survey Division of OPCS. London HMSO, 1993.

Hernandez-Bayo J A, Herranz L, Megia A, Martinez-Olmos M A, Hillman N, Grande C, Pallardo F. Factors related to successful outcome after rapid weight loss in obese patients with NIDDM (Abstract). Int J Obesity 1995, 19, 2, S135.

Hanefeld M, Welk M. Very low calorie diet therapy in obese non-insulin dependent diabetes patients. Int J Obesity 1989, 13, 2, 33-37.

Berg F M. Effectiveness of treatment. Health risks of obesity. Obesity and Health 1993, 85-89.

PDF version: 1-OBESE-PATIENTS-IN-UK-GENERAL-PRACTICES-LOSE-16-TONNES