Vending machines for prescription drugs are already here. How much longer will you be here?If you intend to be a pharmacist of tomorrow, you need to start acting today. Delivering a professional weight management service is a good place to start

By Dr Stephen Kreitzman Ph.D, RNutr and Valerie Beeson, of Howard Foundation Research

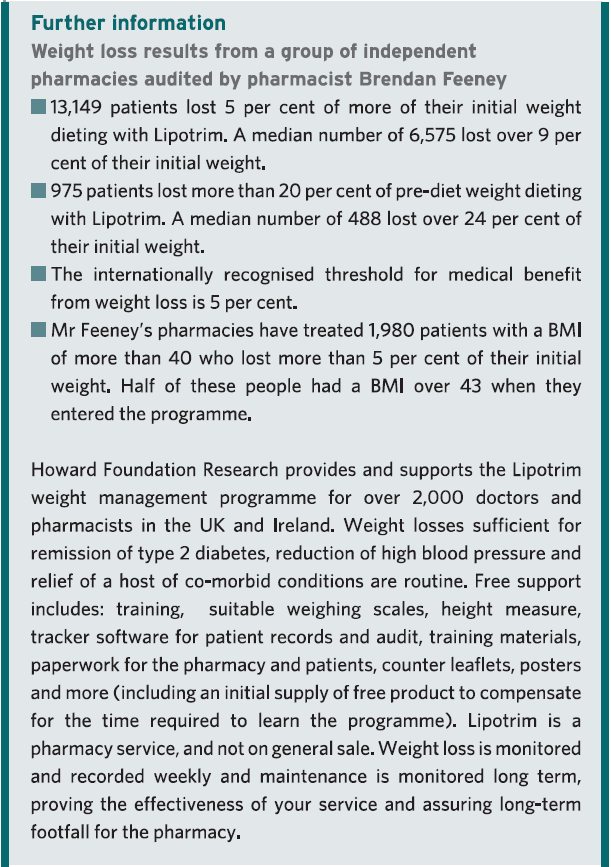

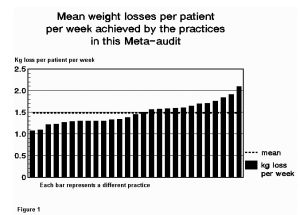

THE ROYAL PHARMACEUTICAL SOCIETY has set out best practice standards for pharmacies delivering public health services in England and Wales. The ‘Professional standards for public health practice for pharmacy’ were created in partnership with the Department of Health, Royal Society for Public Health and Faculty of Public Health, and focus strongly on backing up services with data. They call on pharmacists to ensure their public health offering is evidence-based, tailoring it to local needs wherever possible, and to gather data that proves the value of services

Of all the important services being offered in pharmacy, it could be argued that weight management is the most valuable and documentable. It is valuable because controlling weight prevents and can even treat type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, depression, sleep apnoea, poor fertility and a host of other health issues that are prevalent in the community. It can even impact on services such as smoking cessation, since the possibility of weight gain is often a reason for failure to stop smoking.

A weight management service is readily documentable, since tracker software is available that will instantly provide evidence for weight loss achievements and medical benefits from the weight loss. If you can’t produce data, you have no proof of your pharmacy’s accomplishments.

The not-yet-obese

Treating overweight, but not-yet-obese, people in pharmacy, is obesity prevention on the high street. There are over 30 million overweight and obese people in the United Kingdom. Since no one ever became obese without first being overweight, it is important to provide real help to people at this stage. It is much less problematic to help people who do not have a massive amount of weight to lose and who also do not yet have some of the serious medical consequences associated with excess weight.

Pharmacy has become the prime location for weight management in the UK and Ireland. With the NHS ‘Call to Action’, pharmacy professional bodies are urging pharmacists to make their voices heard and shout about the good they do in improving people’s health.

Helping people lose weight is not just about making them feel good but is also about preventing major long-term health problems, such as type 2 diabetes. A recent article in GP magazine reported a staggering seven-fold rise in insulin use in type 2 diabetes over a nine-year period. An effective pharmacy weight management service could have an enormous and immediate benefit.

But it seems that it’s not just the NHS that needs to hear what pharmacy has to say. The public do, too. North London LPC was inundated with enquiries about a newsletter it had produced raising awareness of pharmacy services in the area.

Promote your service

So what does that mean to you as a pharmacist with a team already offering an established weight management service? Promote your service far and wide and show the public and the NHS what you’ve been doing to improve the health of the nation.

Fin McCaul, for example, is first and foremost a community pharmacist practising in Manchester. He is also the chairman of the Independent Pharmacy Federation and works for Bury CCG one day a week as its long-term conditions lead.

Fin’s passion for independent pharmacy is second only to helping patients lose weight and stop smoking. With an average of 100 quits per year and well over 1,000 patients helped through the weight loss service in his pharmacy, there is nobody better placed to talk about the opportunities and challenges for pharmacy now that public health commissioning has moved into the care of local authorities.

Delegation, motivation and marketing skills and advice for pharmacists and their team are just some of the benefits from his stop smoking/weight loss clinics. At the 2013 Pharmacy Show Mr McCaul organised a series of patient services workshops delivered by pharmacists who were successfully running weight services in their local community and wanted to share their knowledge and expertise. At the March 2014 Independent Pharmacy Federation conference, Fin again provided the opportunity for training in critical pharmacy services and the weight management clinic run by author Valerie Beeson was well attended and appreciated.

A giant change in practice

NHS England’s education arm has launched new standards for pharmacists delivering patient consultations, which have been hailed as a “giant change” in pharmacy practice. Health Education England (HEE) called on pharmacists to ensure they were educating patients, building a relationship with them and respecting their individual needs when conducting consultations.

The Westminster Food and Nutrition Forum seminar, held in London in February, kicked off with the staggering statistic that more than half of the UK population could be obese before 2050. This could create costs of £50 billion a year to the NHS, warned speakers, who included representatives from NHS England, Public Health England, NICE, the Department of Health, CCGs and the nutrition sector.

The speakers agreed that primary care is the key battleground for tackling the issue. But with GPs and pharmacists at the frontline of delivering public health services, who is better placed to keep the nation’s waistline under control? It is clearly pharmacy.

There was no doubt that pharmacy should offer obesity services. Ash Soni, pharmacist and vice chair of the RPS English Pharmacy Board argued that most overweight people did not feel unwell so would usually fail to see the point of visiting their GP. Mr Soni believed using a medical model was the wrong starting point. Most people visited pharmacies for multiple reasons, which presented an “ideal opportunity.”

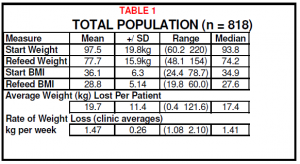

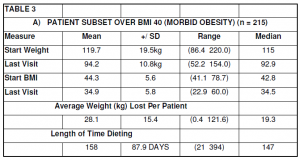

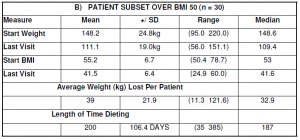

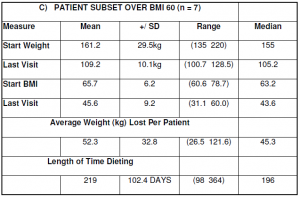

Pharmacy is an excellent provider of weight services for the community. Many overweight people in the BMI 25-30 range take advantage of pharmacy weight loss programmes, recognising that they really work and feeling confident that they are being monitored by healthcare professionals. Pharmacists’ expertise in weight management, however, has proven extremely valuable for the treatment of obese and even morbidly obese people. This is a group who could have qualified for bariatric surgery at great expense and risk.

Effective weight loss absolutely needs to be monitored by knowledgeable healthcare professionals, because real weight loss is not benign. Type 2 diabetics, for example, who lose weight by compliance with a total food replacement diet programme, will induce remission of their diabetes within a few days and continuing with hypoglycaemic medication can result in hypoglycaemia.

There are multitudes of patients taking drugs with a very narrow safety spectrum, such as warfarin or lithium. Dieting can alter the absorption of these drugs, so dosages need to be carefully monitored. There are some people who really should not be dieting at all. Pregnant women, patients with a recent history of surgery, stroke or heart attack are not logical candidates for weight loss.

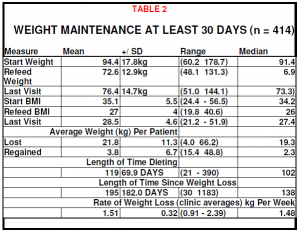

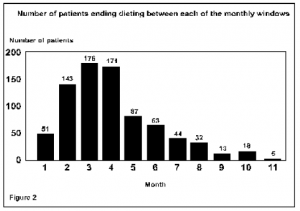

Weight maintenance requires attention and is not usually possible in a busy medical practice. Long-term support in a pharmacy increases the weight maintenance prognosis for dieters.

Now or never

According the the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, it is ‘Now or Never’. “Pharmacists need to become first and foremost providers of patient care, rather than dispensers and suppliers of medicines This is central to securing a future in which the profession can flourish,” it says.

To be a ‘Today’s Pharmacist’ and have your pharmacy remain a valued destination on the high street, start developing and promoting your one-on-one services now. For patients to recognise and value your services, use your consultation room for patient services and not storage space. Be properly equipped for a weight management service by having weighing scales comparable to the ones we provide, that can weigh patients up to 32 stone. Have a chair in the consulting room with no arms that is strong enough to support an obese patient. Be professional, knowledgable, understanding and effective with your weight service.

The pharmacists of tomorrow will have a much greater opportunity to make use of their extensive pharmacy education, long after the vending machines have dominated the prescription business.

PDF Version: todayspharmacist